The best and worst developments in public health have always come from moments of crisis.

In 1937, when the Food and Drug Administration was still a tiny, toothless backwater unable to enforce even basic safety standards for the products under its purview, a new medication called Elixir Sulfanilamide killed 100 or so people in the space of a few weeks. It might have been a minor incident. Fake and faulty medicine was rampant at the time, and accidental poisonings were not uncommon. But many of the elixir victims were very young children, and agency officials wasted no time spinning the incident up into a national crisis. They had already spent decades arguing for tougher laws to hold drug makers accountable. Now, with an anxious and angry populace rallied to their side, they pressed their case — and prevailed. Within a year Congress had passed the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, a regulatory statute that changed the practice of medicine forever.

Some 40 years later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention faced a similarly pivotal moment when several soldiers at Fort Dix contracted swine flu, and one died. Anxious to head off a pandemic and eager to demonstrate their institutional might, agency officials launched a bold but hasty initiative to vaccinate every American against the new virus as quickly as possible. The public grew skeptical of the effort when the vaccines were linked to an extremely rare but serious side effect. And when the threat of a deadly disease outbreak proved vastly overblown, they were outraged. Why foist an untested shot on an entire nation, for a virus that appeared to have sickened just a dozen or so people?

“It was supposed to be this great triumph,” says Joshua Sharfstein, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and author of “The Public Health Crisis Survival Guide.” “But it ended up seeding a generation of vaccine hesitancy instead.” The takeaway from these and similar parables is clear, Dr. Sharfstein says: Crisis can be a powerful catalyst for shaping policy and improving society. But just like any such tool, it can be misused as easily as used.

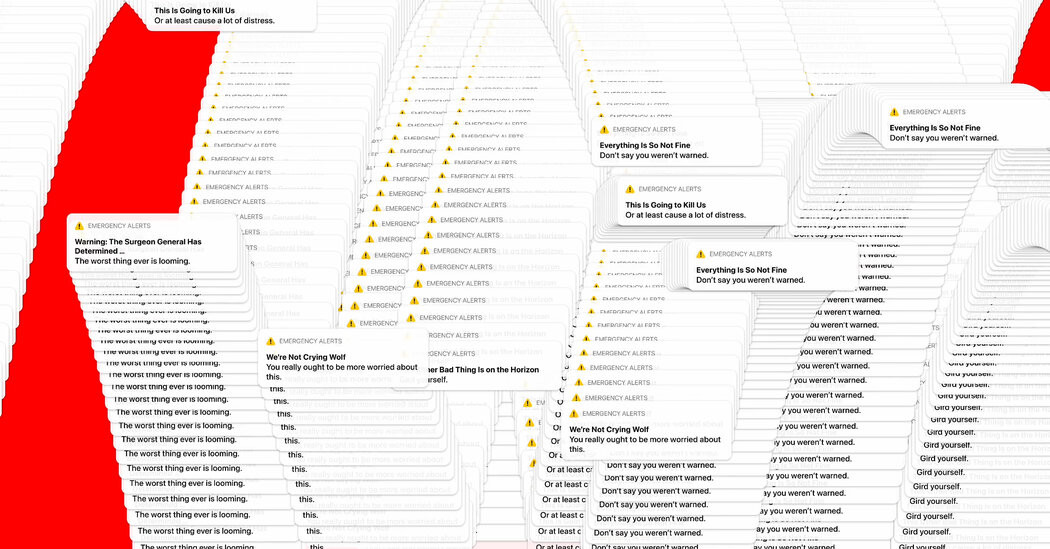

If that lesson isn’t new, it’s very much worth reviewing now. The United States is in what can only be described as an epoch of crisis. There is no quarter of American life that has not been claimed by the term, from the planet (climate) to the Republic (democracy, migration, housing) and the deepest chambers of the human heart (loneliness, despair). In the future, if we survive that long, historians will marvel at either our capacity to endure so much hardship at once or our ability to label so many disparate problems with the same graying word. In the meantime, officials and policymakers — and, yes, journalists — ought to consider how they employ this term and why, and whether it’s having the desired effect.

There’s no better place to start than with public health. Two centuries back, when infectious disease outbreaks still routinely devastated the nation’s most populous cities, the practices needed to protect the health of whole communities were an accepted (occasionally celebrated) part of the social contract. But public health has long since fallen victim to its own success: As plagues receded and life expectancy rose, support for the initiatives that made those achievements possible waned. And as clinical medicine improved, health itself became a matter for individuals, not for society at large.

Since the turn of the previous century, the national approach to public health has been governed by a cycle that experts refer to as neglect, panic, repeat. Elected officials ignore the nation’s public health apparatus — they starve it of funding and isolate it from the larger, more stable health care system — until a crisis or panic of some kind emerges. Then they flood that apparatus with resources, and a mad scramble begins not only to resolve the current crisis, but also to repair the many flagging structures most essential to that effort. Public health experts like to call this building the plane while flying the plane.

.StoryBodyCompanionColumn > div:first-of-type strong, p.ParagraphBlock-paragraph strong, article.article div p strong, article.nytapp-hybrid-article div p strong {

font-size: 90px;

font-family: nyt-cheltenham-cond;

font-weight: 800;

float: left;

line-height: 1;

margin-right: 12px;

margin-top: 8px;

margin-bottom: -15px;

}

.opstoryline-wrapper strong{

font-size: 13px !important;

font-family: “nyt-cheltenham” !important;

letter-spacing: 0.5px !important;

text-transform: uppercase !important;

font-weight: 600 !important;

color: #333 !important;

-webkit-font-smoothing: antialiased;

line-height: 23px !important;

margin-top: 0 !important;

margin-bottom: 0 !important;

margin-right: 0px !important;

float: none !important;

}

@media screen and (max-width: 720px){

.StoryBodyCompanionColumn > div:first-of-type strong, p.ParagraphBlock-paragraph strong, article.article div p strong, article.nytapp-hybrid-article div:not(‘.opstoryline-wrapper’) p strong {

font-size: 75px;

}

}