From ancient star streams to the innards of white dwarfs, the Gaia space telescope has seen it all.

On Thursday, mission specialists at the European Space Agency will send Gaia, which is low on fuel, into orbit around the sun, and switch it off after more than a decade of service to the world’s astronomers.

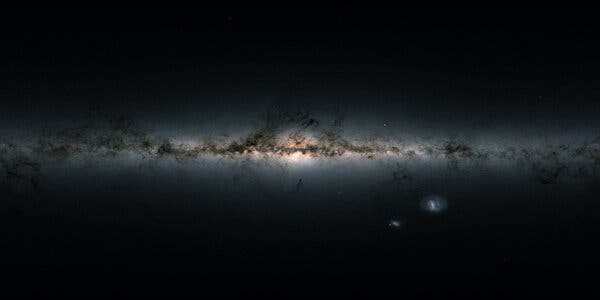

Gaia has charted the cosmos since 2014, creating a vast encyclopedia of the positions and movements of celestial objects in our Milky Way and beyond. It is difficult to capture the breadth of development and discovery that the spinning observatory has enabled. But here are a few numbers: nearly two billion stars, millions of potential galaxies and some 150,000 asteroids. These observations have led to more than 13,000 studies, so far, by astronomers.

Gaia has transformed the way scientists understand the universe, and its data has become a reference point for many other telescopes on the ground and in space. And less than a third of the data it has gathered has so far been released to scientists.

“It’s something that is now underpinning almost all of astronomy,” said Anthony Brown, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands who leads Gaia’s data processing and analysis group. “I think if you were to ask my astronomy colleagues, they couldn’t imagine anymore having to do research without Gaia being there.”