It’s been said that Nelson Rockefeller, who as a grown-up managed the opening of Rockefeller Center, the real estate colossus in Midtown Manhattan, liked to play with blocks as a boy: the ones between 49th and 55th Streets.

In fact, according to his most recent biographer, Richard Norton Smith, Nelson was “less concerned with Rockefeller Center’s commercial prospects than its artistic possibilities” (notwithstanding his eradication of a Diego Rivera mural there in 1934 after the artist defiantly superimposed a profile of Lenin).

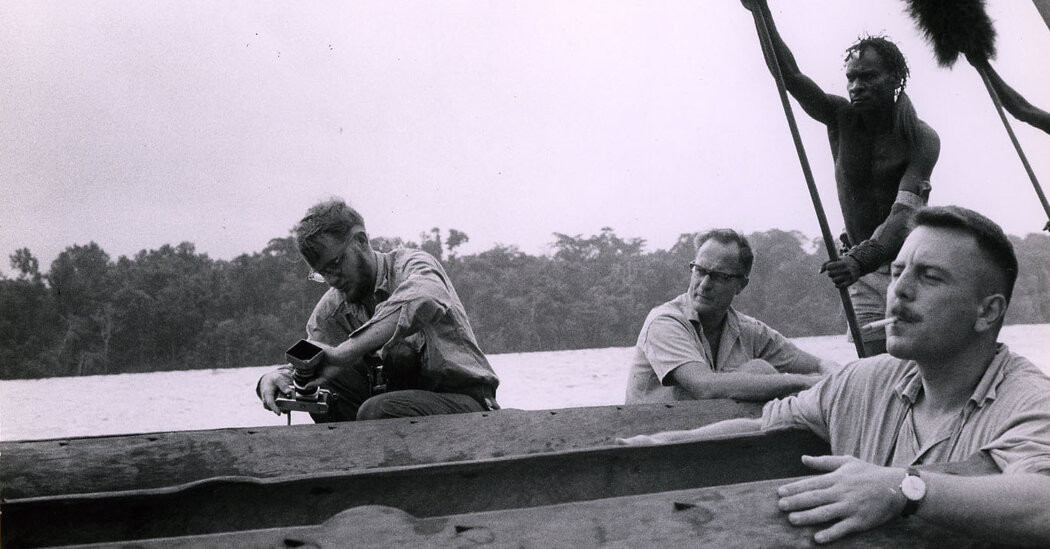

Rockefeller, who was elected governor of New York four times and was Gerald R. Ford’s vice president, was infatuated with sui generis objects of art. He defined their value not by their provenance or price or the artist’s cachet, but simply by what he liked.

Inspired by Brasília, he created a new Capitol complex in Albany. He commissioned Picasso to produce tapestries, including one that hung in the boathouse of his vacation home in Seal Harbor, Maine, which he proudly showed off for visiting reporters after he was nominated to the vice presidency.

His first childhood love, he once said, was a marbled Bodhisattva — a figure of a Buddha — from the Tang Dynasty. (At his request, his mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, left it to him in her will.) On his eighth birthday, he asked for Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, one of the few objects on his wish list that proved to be inaccessible; the 16th-century painting remains in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden.

What his mother did for her trove of underappreciated American folk art by establishing a museum in Williamsburg, Va., as well as helping to found the Museum of Modern Art, Nelson Rockefeller did for Indigenous paintings and sculpture. He triggered a cultural revolution that elevated so-called primitive art from objects relegated to discreet ethnographic collections to their proper place as an integral component of global human creativity.