The Supreme Court’s conservative bloc reduced the power of district court judges to block government actions nationwide.

The Supreme Court on Friday allowed President Trump’s executive order restricting birthright citizenship to take effect in some parts of the country for now, ruling that several district court judges had exceeded their authority in blocking the policy across the country.

The court stressed that its ruling did not address the constitutionality of Mr. Trump’s order itself, which bars government agencies from automatically treating babies as citizens if they were born on domestic soil to undocumented migrants or foreign visitors without green cards.

Rather, it focused on so-called universal injunctions, a tool by which district courts could impose a nationwide freeze on executive branch policies that have faced legal challenges. Such injunctions applied broadly, extending to people who are not plaintiffs in the lawsuits challenging those actions. Those types of injunctions were once rare, but had become increasingly common in recent years.

The ruling was 6 to 3, split along ideological lines.

Here are some highlights.

The majority opinion, written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, held that the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, which created lower courts, does not give district court judges the power to issue preliminary injunctions granting relief to people other than the plaintiffs before them. The rest of the conservative wing — Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh — joined her opinion, which concluded:

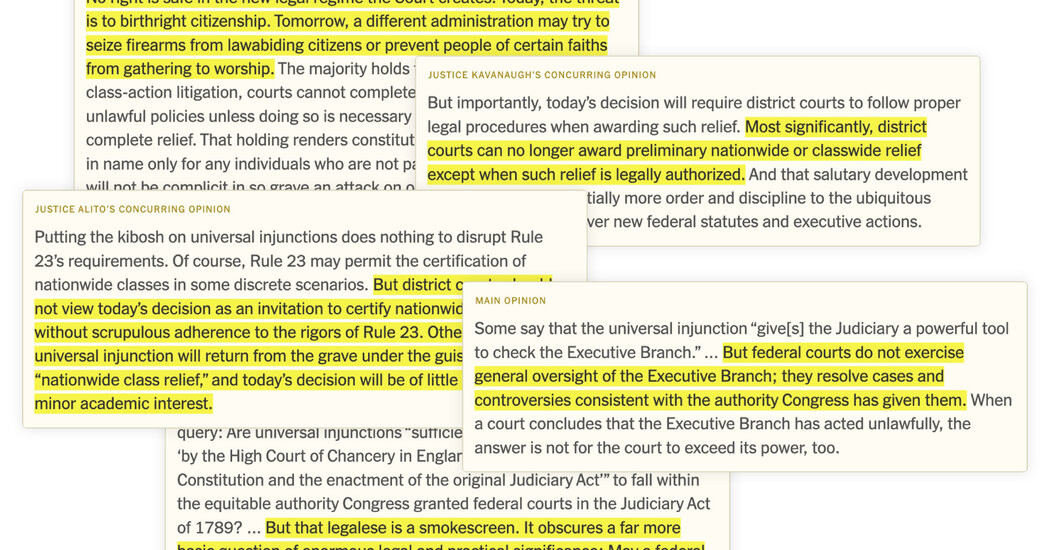

Some say that the universal injunction “give[s] the judiciary a powerful tool to check the executive branch.” … But federal courts do not exercise general oversight of the executive branch; they resolve cases and controversies consistent with the authority Congress has given them. When a court concludes that the executive branch has acted unlawfully, the answer is not for the court to exceed its power, too.

The dissent was written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who summarized her argument from the bench, a rare step that signals profound disagreement. The opinion, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, asserted that the majority’s ruling would allow the government to play games with constitutional rights:

No right is safe in the new legal regime the court creates. Today, the threat is to birthright citizenship. Tomorrow, a different administration may try to seize firearms from law-abiding citizens or prevent people of certain faiths from gathering to worship. The majority holds that, absent cumbersome class-action litigation, courts cannot completely enjoin even such plainly unlawful policies unless doing so is necessary to afford the formal parties complete relief. That holding renders constitutional guarantees meaningful in name only for any individuals who are not parties to a lawsuit. Because I will not be complicit in so grave an attack on our system of law, I dissent.

In the majority opinion, however, Justice Barrett countered that nationwide relief could still be obtained through class-action lawsuits. Noting that there are limits on when judges can certify a class, which are found in Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, she added that universal injunctions had evolved into an improper workaround of such limits.

Rule 23’s limits on class actions underscore a significant problem with universal injunctions. A “‘properly conducted class action,’” we have said, “can come about in federal courts in just one way—through the procedure set out in Rule 23.” … Yet by forging a shortcut to relief that benefits parties and nonparties alike, universal injunctions circumvent Rule 23’s procedural protections and allow “‘courts to “create de facto class actions at will.”’” … Why bother with a Rule 23 class action when the quick fix of a universal injunction is on the table?

Lower courts should carefully heed this court’s guidance and cabin their grants of injunctive relief in light of historical equitable limits. If they cannot do so, this court will continue to be “duty bound” to intervene.

Putting the kibosh on universal injunctions does nothing to disrupt Rule 23’s requirements. Of course, Rule 23 may permit the certification of nationwide classes in some discrete scenarios. But district courts should not view today’s decision as an invitation to certify nationwide classes without scrupulous adherence to the rigors of Rule 23. Otherwise, the universal injunction will return from the grave under the guise of “nationwide class relief,” and today’s decision will be of little more than minor academic interest.

Second, if one agrees that the years-long interim status of a highly significant new federal statute or executive action should often be uniform throughout the United States, who decides what the interim status is? The answer typically will be this court, as has been the case both traditionally and recently. This court’s actions in resolving applications for interim relief help provide clarity and uniformity as to the interim legal status of major new federal statutes, rules and executive orders.

To hear the majority tell it, this suit raises a mind-numbingly technical query: Are universal injunctions “sufficiently ‘analogous’ to the relief issued ‘by the High Court of Chancery in England at the time of the adoption of the Constitution and the enactment of the original Judiciary Act’” to fall within the equitable authority Congress granted federal courts in the Judiciary Act of 1789? … But that legalese is a smokescreen. It obscures a far more basic question of enormous legal and practical significance: May a federal court in the United States of America order the executive to follow the law?