An Afghan tech worker in California now faces a prolonged separation from his wife, who he had hoped would soon join him in America. A Somali American filmmaker in Minnesota has become afraid to do what he is legally able to, travel abroad. A refugee from Afghanistan in Idaho worries that she will be stereotyped as a terrorist in her adopted home.

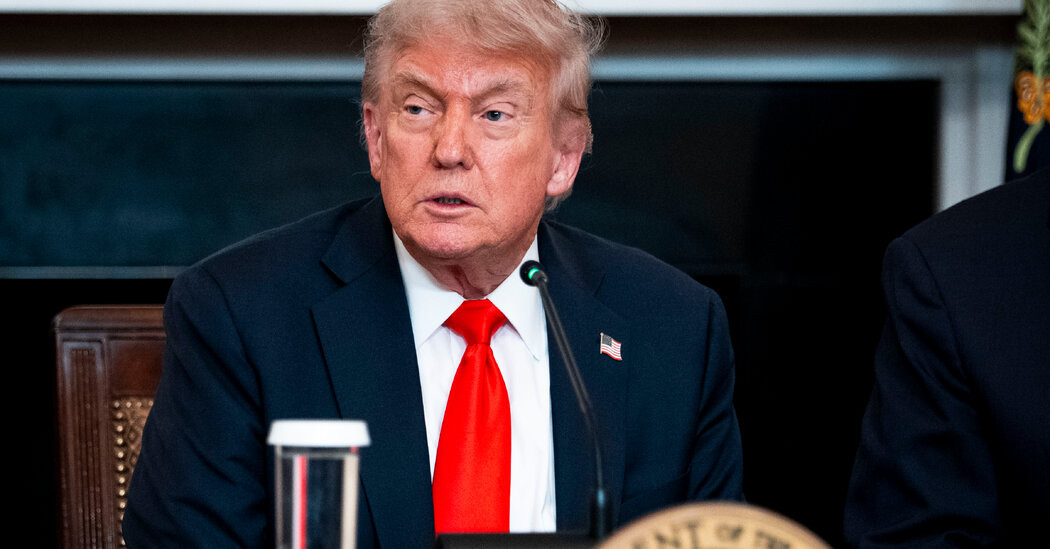

President Trump signed an order on Wednesday barring citizens of a dozen countries, primarily in Africa and the Middle East, from traveling to the United States. Immigrants from those countries said they were not surprised by the president’s move — on the campaign trail, he had promised repeatedly to revive the contested travel bans from his first term — but nonetheless described being hurt and confounded.

“I don’t understand why the president has to target us nonstop,” said Frantzdy Jerome, a Haitian asylum seeker with a work permit who works the overnight shift at an Amazon warehouse in Ohio.

There was widespread fear and confusion in immigrant communities across the nation, in big cities with bustling African and Middle Eastern enclaves, and in small towns where clusters of refugees and immigrants were gaining footholds in their new homes.

Those from the affected countries said the ban would wrench families apart by upending travel plans and immigration cases. They said they worried that the ban would foment distrust and hostility toward Muslims and others from the targeted places. And they said that economic and business relationships would be cut off.

The ban is scheduled to go into effect on Monday, and bars travel to the United States by citizens of Afghanistan, Myanmar, Chad, the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. There are some exemptions, including for those who have existing visas or green cards that allow them to live in the country.

Still, officials and community organizations said that they had been inundated by questions, and that they were advising caution. The Los Angeles-area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations quickly released a list of guidelines for those who might be affected: Talk to an immigration attorney, keep important documents “handy and secure,” avoid travel unless it is essential, and stay up-to-date on your rights.

At the Raayan African grocery store at a strip mall in Twin Falls, Idaho, the Somali owner shook his head in disbelief.

“Trump is going to do whatever he wants,” said Abdulwahabu Mukomwa.

Mr. Mukomwa, 40, arrived in the United States in 2013 after living in a refugee camp in Kenya for more than 10 years. Now, he sells cassava root and flour, as well as an array of food, beauty products, clothes and incense that cater to Twin Falls’s thriving refugee community.

“The more you listen,” he said of Mr. Trump, “the more you risk losing your mind.”

One of his customers, Yasser Hamed, a refugee from Sudan, said he learned about the new travel ban on TikTok.

“It’s sad, really sad, when you hear your country is on the list of people they are not welcoming to the United States,” said Mr. Hamed, 40. He has been in the country for more than a decade, runs his own trucking business and is married with three U.S.-born children.

Another customer, the Afghan refugee who worries about being stereotyped, declined to share her name out of fear of retribution, as she bought goat meat, cookies and a yogurt drink. “I know there are terrorists in my country, but we are not all terrorists,” she said. “There are good people and bad people everywhere.”

In Minnesota, where the large Somali diaspora has become an influential cultural and political force, news of the ban on travel to many residents’ home country cast a pall of dread.

“It’s antithetical to what America stands for,” said Hamse Warfa, an entrepreneur who’s based in the Twin Cities region of Minneapolis and St. Paul and who served as a senior adviser in the State Department during the Biden administration. “This is a country with a long history of welcoming strangers, including those who are now in positions of leadership.”

The Twin Cities received thousands fleeing Somalia’s civil war in the 1990s. Since then, Somali community members have enriched Minnesota’s food scene and civic life. In 2018, Representative Ilhan Omar, a Democrat whose district includes Minneapolis, became the first member of Congress from Somalia.

Abdi Mohamed, 31, the Somali American filmmaker in Minneapolis, said the policies might put an end to the initiatives he has led to foster deeper ties between Somali Americans and Somalis back home.

“To cut us from our homeland is the worst thing to somebody,” said Mr. Mohamed, who was born in a refugee camp in Kenya and immigrated to the United States as a baby.

Despite being a U.S. citizen and legally able to travel to Somalia, he said he was uncertain whether it would be safe to do so.

“There’s bewilderment and fear not knowing whether you’re going to get in trouble — or even for what,” Mr. Mohamed said.

Some immigrants who have been in the United States for decades were more willing to give Mr. Trump the benefit of the doubt. In Brooklyn’s Little Haiti, Dolores Murat, a business owner who was born in Haiti and moved to New York almost four decades ago, said that barring travel from her conflict-ridden home country seemed justified.

“The bottom line is it doesn’t fall under President Trump to make Haiti safe,” Ms. Murat said. “It falls under the Haitian government to make Haiti safe for their own people. I think it’s right to do what he’s doing for his country.”

In a section of West Los Angeles where the hub of the large Iranian community is known as Tehrangeles or Persian Square, some immigrants were skeptical that a ban would last.

Roozbeh Farahanipour, 54, who came to America more than 20 years ago to flee political persecution by the government of Iran, wondered if the ban was a negotiating tactic to put pressure on Tehran over its ambitions to build a nuclear weapon.

Still, Mr. Farahanipour, who owns multiple businesses in the area and is the chief executive of the West Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, worried that the ban might close the door on others following in his footsteps.

“I came here with nothing,” Mr. Farahanipour said, adding, “I don’t want to be the last American dream.”

Mohammad Ghafarian sat a couple of storefronts away at the counter of the bakery he owns, waiting for his afternoon cup of Persian tea to cool.

Mr. Ghafarian, who owns the Shater Abbass Bakery & Market, said that he and other merchants relied on Iranian tourism, and that the travel ban might hurt business.

“I’m selling Persian groceries and Persian merchandise,” said Mr. Ghafarian, who first left Iran for Canada in the 1970s before moving to the United States. “But if there is not much Persian, I won’t have good business.”

Sahil, the tech worker from Afghanistan in California, arrived in the United States in 2022, after two of his brothers obtained special immigrant visas for helping the American military. He asked to be identified only by his first name out of fear for his wife’s safety. She had to remain in Afghanistan while the Taliban swept into power.

“I was trying to calm her down and give her hope,” he said. “I said, ‘You will come to the United States, you will be able to work and study.’”

He stayed up until dawn deliberating how to break the news to her about the new ban. “I don’t know how to tell her,” he said, “that it is going to take years to bring her here.”

Jazmine Ulloa and Ana Ley contributed reporting.

![Enjoy the [Road] Show Travel Mug with Handle, 14ozEnjoy the [Road] Show Travel Mug with Handle, 14oz](https://georgemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/479070202831754764_2048-300x300.jpeg)