When it comes to “nationalizing” elections, both parties are constitutional purists until they are not.

Federalism is treated as sacred, right up until it becomes an obstacle to winning elections. Then the Constitution’s Elections Clause is rediscovered, Congress suddenly has sweeping authority, and Washington, D.C., must step in to save democracy from the states. The only thing that changes from cycle to cycle is which party is making variations of this argument. And that usually depends on who is in power.

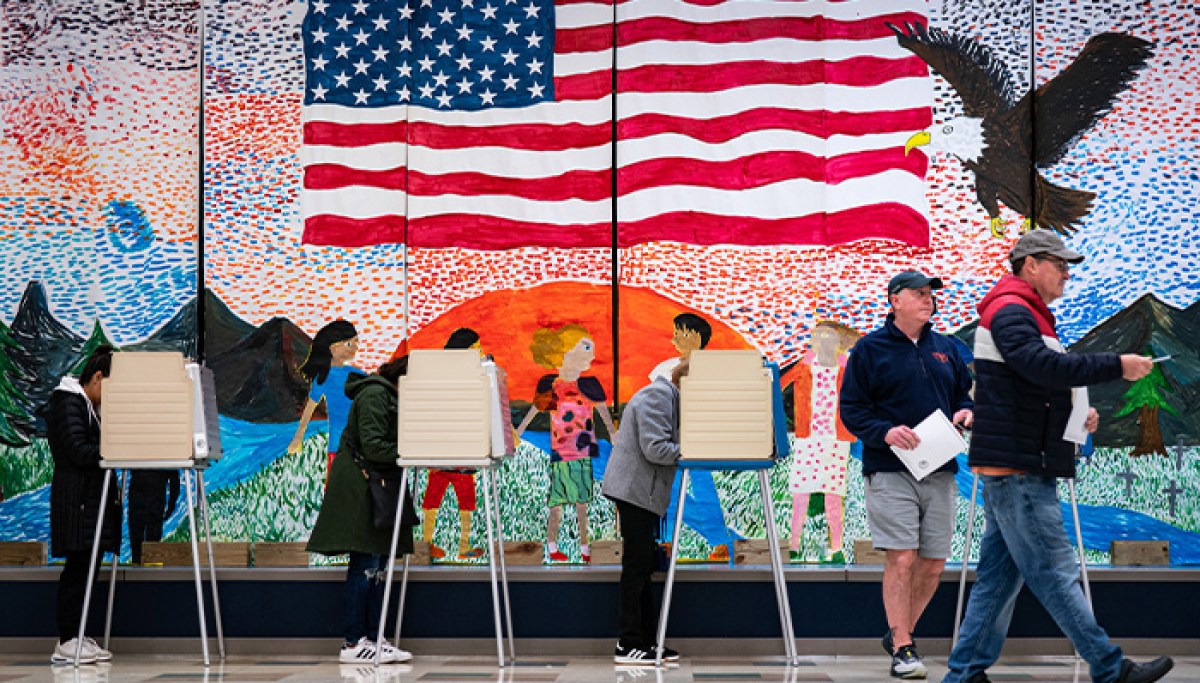

President Donald Trump’s recent call to “nationalize the voting” makes that dynamic very visible. In a Feb. 2 interview with podcaster Dan Bongino, until recently his administration’s deputy FBI director, urged Republicans to “take over the voting” in “at least many, 15 places.”

Trump, with the midterm elections approaching in his second, nonconsecutive term, added, “The Republicans ought to nationalize the voting.”

Naturally, Democrats reacted as if he had proposed suspending the Constitution. Many Republicans heard something else: a call for uniform national standards in response to what they argue are weaknesses in state-run systems.

The rhetoric might be dismissed as typical Trumpian bloviating if it were not paired with legislation and executive signaling. The House has passed the SAVE America Act, which would require documentary proof of American citizenship to register to vote in federal elections and impose a nationwide photo ID requirement to cast a ballot.

The bill would also prohibit the automatic distribution of mail ballots to all registered voters and require an application before a ballot is sent. That change would directly affect eight states and Washington, D.C., which use mailing ballots to registered voters as their default election method. And while the proposal would not eliminate no-excuse absentee voting, it would end automatic ballot mailing in jurisdictions that rely on it.

Supporters describe the measure as a straightforward integrity reform. Critics maintain it would force structural changes in states that have administered all-mail systems for years and add bureaucratic burdens in the name of fraud prevention. Either way, it is unmistakably a federal standard imposed on state-run systems.

Trump has also said he would seek to require voter ID for the November midterm elections “whether Congress approves them or not,” promising executive action without identifying the legal basis. That threat comes from his “I have an Article II. I can do whatever I want,” thought process. It is one thing for Congress to legislate under its authority under the Elections Clause. It is another for a president to announce that he intends to impose nationwide election rules first and resolve the legality afterward. It is a declaration that executive power may substitute for the legislative process, a practice that has become all too common in present-day governance.

The administration’s enforcement posture offers another layer. The White House has said there are no formal plans to deploy Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to polling sites. Still, officials have declined to guarantee that federal agents will not be present near voting locations. In isolation, that could be dismissed as political theater. In context, it reinforces the Democratic warning that “nationalizing” elections might mean not just uniform standards but also a possible federal presence, which would undoubtedly be cast as intimidation.

A recent episode in Georgia shows why such concern exists. In early February, Fulton County officials challenged the FBI’s seizure of 2020 election records from local offices. The warrant in the county covering most of Atlanta was tied to allegations of irregularities in the 2020 vote, claims rooted in the stolen-election story that Trump continues to promote today. He remains the most prominent advocate of the view that the 2020 result was illegitimate. When a president who still disputes his loss speaks of “nationalizing” voting while federal authorities seize election materials from a jurisdiction central to that dispute, it is not unfair for critics to suspect partisan gamesmanship.

Republicans defend their position by pointing to the constitutional text. Article I, Section 4 provides that states shall prescribe the “Times, Places and Manner” of holding congressional elections, but that Congress may “make or alter” such regulations. That clause has long undergirded federal voting-rights statutes and national election standards.

On that basis, Republicans argue that proof-of-citizenship requirements, uniform ID rules, and limits on automatic mail-ballot distribution for federal elections fall squarely within congressional authority. National elections, they contend, require national baselines. In their view, the SAVE Act is not a federal takeover but a federal safeguard.

For Republicans, the issue is not the constitutional clause. It is the memory of their own arguments. For years, they warned that Democrats were attempting to federalize elections in ways that would override state policy choices and benefit one party.

During former President Joe Biden’s single term, Democrats advanced H.R. 1, the For the People Act, as a sweeping rewrite of federal election administration. The bill would have mandated at least 15 consecutive days of early voting nationwide for federal elections. It would have required states to permit no-excuse mail voting, provide prepaid postage for ballots, and restrict the grounds for rejecting mail ballots.

The proposal would also have required states to allow voters without acceptable photo identification to sign affidavits to cast ballots. It included automatic voter registration and same-day registration for federal contests. And it would have required congressional redistricting by independent commissions rather than state legislatures.

Democrats did not approach this proposed shift of power from the states to the federal government in running elections reluctantly. They explicitly argued that Congress had broad authority to regulate federal elections and that Washington needed to override restrictive state laws to “protect democracy.” In practice, H.R. 1 would have nationalized major elements of election administration across all 50 states.

Republicans denounced the bill as a power grab that would displace state control and tilt the playing field toward Democratic constituencies. Their warnings were saturated with federalism language, with repeated insistence that Washington should not dictate how local officials run elections.

Now, the positions are inverted.

Democrats who once insisted Congress had expansive authority to impose uniform national standards now lean heavily on the principle that states run elections. They warn that Trump’s rhetoric about “taking over” voting, combined with executive-order talk and the prospect of federal agents near polling places, threatens the decentralized structure embedded in the Constitution.

Republicans who framed H.R. 1 as an assault on federalism are advancing a federal proof-of-citizenship mandate, curtailing automatic mail-ballot distribution, and entertaining the idea that executive authority can be used to reshape election procedures without waiting for legislation.

There are exceptions. Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) opposed “nationalizing elections” when Democrats were in control and has expressed discomfort with similar rhetoric now. A small group of Republican institutionalists who objected to H.R. 1 on federalism grounds has not entirely abandoned that position, including Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD). They demonstrate that consistency is possible, if very uncommon, in today’s political climate.

The constitutional text has not changed. The Elections Clause still gives states the primary responsibility for administering federal elections, subject to congressional alteration. What shifts is which party believes national standards will serve its interests at a given moment.

When Democrats believed that uniform early-voting mandates, expanded mail voting, and redistricting commissions would blunt Republican advantages in state legislatures, they adopted nationalization as a means of protecting democracy. When Republicans believe that proof-of-citizenship mandates, nationwide ID rules, and restrictions on automatic ballot distribution will strengthen confidence and constrain permissive systems in blue jurisdictions, they embrace nationalization as an election integrity measure.

TRUMP RAISES NATIONALIZED VOTING IDEA IN BONGINO’S RETURN PODCAST DEBUT

The language of principle follows the incentives.

“Nationalizing elections” is less a radical innovation than a rotating justification. The players change. The incentives do not.

Jay Caruso (@JayCaruso) is a writer living in West Virginia.

Discount Applied Successfully!

Your savings have been added to the cart.