Business franchising in America continues to increase, with almost a solid decade of recent growth. The number of franchise establishments grew from 697,943 in 2013 to 806,270 a decade later, and will rise to an estimated 821,589 establishments this year, according to Statista data.

Franchised businesses are often stereotyped as fast-food establishments. The type of businesses that are franchised run the gamut from, yes, food (McDonald’s, Popeyes) to hardware (ACE) to hospitality (Red Lion) to haircuts (Great Clips) to animal care (Woof Gang Bakery and Grooming), and so much more. These are boom times for franchise branding.

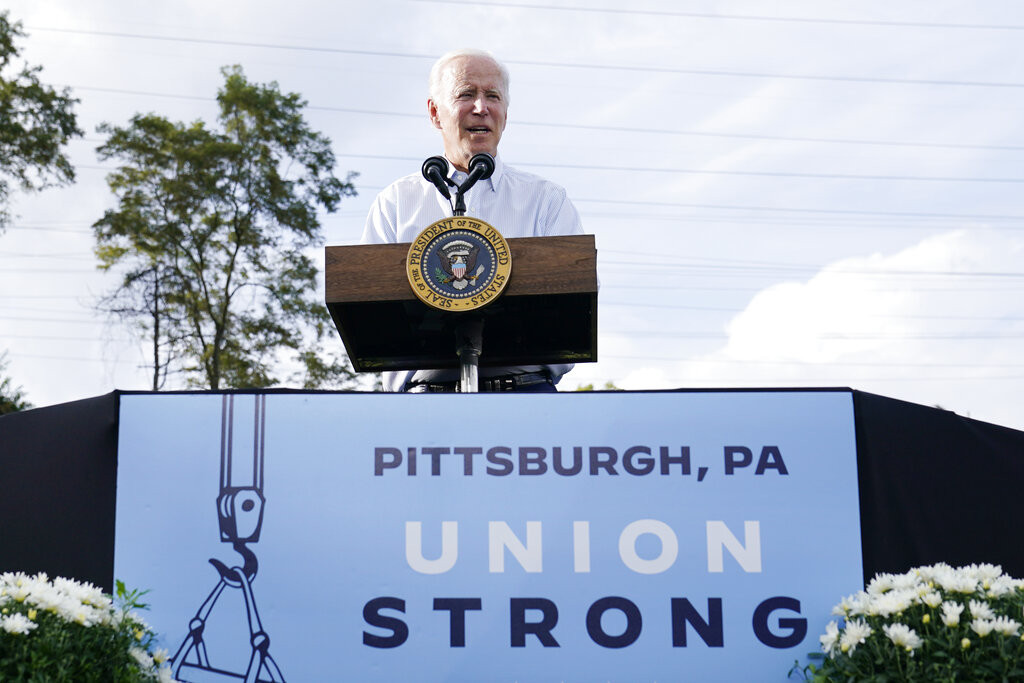

This is doubly impressive when you consider that two different recent presidential administrations have pushed changes that would cut franchising down to size. Both former President Barack Obama and President Joe Biden‘s administrations have tried to pass something called the joint employer rule through the National Labor Relations Board, as a sop to trial lawyers and organized labor.

If it is implemented, critics charge that the joint employer rule would open franchisers, the companies that create the brands, to greater liability and mass unionization drives. It would also likely cut down on the profitability and autonomy of franchisees, the smaller businesses that rent those brands. It could burden other industries as well, but the challenges to franchising border on existential.

How have franchises managed significant growth in spite of regulatory efforts aimed at the heart of their business model? It doesn’t hurt that majorities in Congresses have objected to these efforts, one industry representative said.

“We are grateful to the bipartisan majority in Congress who have stood up for franchising against the NLRB’s joint employer rule,” Michael Layman, senior vice president of government relations for the International Franchise Association, told the Washington Examiner. “Three times Congress voted to nix this harmful policy.”

Most recently, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted to invoke the Congressional Review Act and disapprove of the new rule by a vote of 207 to 177. The Democratic-controlled Senate agreed to the resolution by a vote of 50 to 48. The bill landed on the Oval Office desk on May 1.

Layman added, “President Biden’s decision to stand with the NLRB and against small businesses shows where his support lies.”

In vetoing the CRA resolution, which would have canceled the joint employer rule, President Joe Biden argued in a statement that the rule will “prevent companies from evading their bargaining obligations or liability when they control a worker’s working condition — even if they reserve such control or exercise it indirectly through a subcontractor or other intermediary.”

The president explained, “If multiple companies control the terms and conditions of employment, then the right to organize is rendered futile whenever the workers cannot bargain collectively with each of those employers.”

Congress then tried and failed to override Biden’s veto. Whether or not supplying, say, uniforms and signage and milkshake machines really counts as “control[ling] a worker’s working condition” then became a matter for courts to sort out.

Thus far, the rule isn’t faring well in the judiciary. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce sued the NLRB. United States District Court Judge for the Eastern District of Texas J. Campbell Barker vigorously criticized and vacated the rule in a March 8 ruling.

Barker found that NLRB had “largely backhanded and thus failed to reasonably address the disruptive impact of the new rule on various industries.” Franchised businesses, for instance, had about $825 billion of economic output in 2022, and more than 8 million workers.

The judge wasn’t willing to upset that economic apple cart based on what he found to be the government’s flimsy rationale. He argued that the rule “runs headlong” into Supreme Court precedent and “exceeds the bounds of the common law.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The NLRB can appeal Barker’s ruling, but it may not fare better in other courts or in the U.S. Supreme Court down the road.

If the joint employer rule does finally go away, most folks in the franchise industry will likely breathe a sigh of relief and then quickly get back to work. There’s a great deal of food to be made, rooms to be rented, hair to be cut, and goods to be sold.